By 1984, two of the big ‘unholy trinity’ of 80s slasher franchises, Halloween and Friday the 13th, had already been established. Wes Craven was late to the party, but he brought with him the film that would not only complete the slasher picture but would also birth the franchise that arguably became the biggest pop culture phenomenon of them all: A Nightmare on Elm Street.

For all the love, though, of Freddy Krueger as the wise-cracking, charismatic purveyor of ever-more comical and fantastical death-dreams, the original A Nightmare on Elm Street was an altogether darker, more thoughtful, more satisfying affair, with a Freddy Krueger that was driven less by his own self-amusement, and more by his insaitable need to kill children, and for revenge against their parents.

This is a film about vulnerability and internal trespass; the mystery and power of dreams; the self-control required to overpower your torments; and it all starts with an act of vigilante justice in the suburbs by the parents of Elm Street…

A Murderous Myth is Born

The instigating incident for the mythology of the Elm Street franchise is well-known: Fred Krueger (not yet the more friendly-sounding ‘Freddy’) was a child murderer (and implied paedophile —not made concrete here but certainly suggested), who took away and murdered twenty children from the neighbourhood around Elm Street. Krueger was freed on a technicality—a warrant was signed incorrectly—and the local parents, incensed at this, tracked Krueger down to the abandoned boiler room he took his victims to and set the place on fire in a moment of righteous retribution, burning Krueger to death in a forced atonement for his monstrous sins.

It’s a fascinating backstory, one which reveals several layers on inspection. Firstly, Krueger is not given here any particular motive for his crimes, nor do we get any further personal information or backstory for him other than that he used to take his victims to a boiler room. We do not know why Krueger kills, why specifically he kills children, or what he did outside of his killings: his job or relationships, for example.

The franchise would go on to paint sometimes contrasting ideas about Freddy’s background, but here, Fred Krueger is presented as simply all id, a big burning ball of impulse and desire, insatiable appetite, all action and no thought. The most we can say is he is not above taking revenge, and he takes great pleasure in his ‘work’. He is the killing instinct made flesh, and he is terrifying because relentless violence without consideration cannot be reasoned with.

A Creature of Inner Tresspass

In fact, outside of Wes Craven’s A New Nightmare, Freddy is probably at his most sinister and frightening in this film. Part of that comes down to how he uses his body—literally. In pursuit of terrorising the children of Elm Street, the Freddy of A Nightmare on Elm Street literally makes the children watch him self-harm while he laughs about it. He cuts his own finger off, the wound spurting out green, putrid blood; he takes off his ‘face mask’ of burnt flesh to reveal…well, even more burnt flesh; he cuts his chest, and we see that his insides are infested with writhing maggots. If the nightmares the characters experience in the film function as a kind of decay of innocence, then Freddy and his wounded, polluted body are the physical embodiment of that decay.

It frightens both the children and us for two key reasons: one, the sight of someone mutilating themselves is never pretty, to say the least; and two, it plants the idea that, if Freddy is willing to do this to himself, what is he willing to do to other people?

And then there’s the sounds of the scraping of blades and distant laughter as teenagers traverse their nightmares, looking for either escape or the source of discomfort. This is a Freddy that watches from the shadows, that intimidates at first through suggestion—eerie noises, whispered curses. He’s a monster that likes to set a murderous mood first before going in for the kill. And by the time he does so, both the audience and the dreamer are on the verge of shattered nerves.

In fact, the Freddy Krueger character has a link with Dracula in a way. He comes to his victims while they sleep, usually in their beds. Now, your bed is supposed to be your safe haven, your most intimate, vulnerable space, where, by falling asleep, you let go. Both Krueger and Dracula invade this vulnerable space. Dracula would enter the bedroom of women and penetrate them with his teeth: a form of physical trespass. Freddy, though, trespasses internally. He invades the mind of the sleeper, probing and assaulting them in their subconscious —perhaps an even more intimate a tresspass than Dracula’s.

This is a Freddy who has yet to discover his verbosity, and while less charismatic, he makes up for it in sheer creepiness. Stalking his boiler room, he whispers and almost croons simple, childlike phrases like “gonna get you!”, as if playing a perverted game of hide and seek with his victims. Even when he does make a witticism, it’s designed to abuse rather than amuse. Take, for instance, the moment Nancy answers her unplugged phone, unnerving enough in itself, only for the mouthpiece to turn into Freddy’s predatory mouth and tongue. “I’m your boyfriend now, Nancy” is arguably a lot more sinister than the later “wanna suck face?” from A Nightmare on Elm Street 4. There is violent intent behind the line here.

But it’s not just Freddy/Fred who is different in A Nightmare on Elm Street. So are the dreams that he stalks.

Dream a Little Dream of Death

The great thing about having a monster that kills its victims by stalking their dreams as your central premise is that the use of dreams opens up a whole world of creative ideas and imagination when it comes to how these can be deployed in the film, both visually and thematically.

A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors arguably exemplifies this best, using the dreams to visually depict the characters’ deepest inner desires and torments only for Freddy to turn these against the dreamers and obliterate them. Take Jennifer, for instance, dreaming of becoming an actress and watching a chat show interview for tips, only for Freddy to sprout out of the TV and drive her headfirst through the screen. Or Taryn, haunted by her struggles with drug addiction, only for Freddy to kill her by turning his blades to syringes and injecting her.

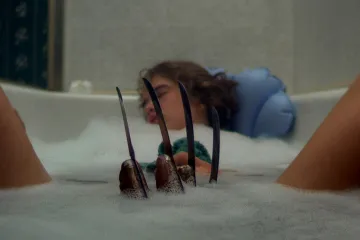

When considered in this way, the dreams in the original A Nightmare on Elm Street are notable for how grounded they are. Neither Freddy nor the dreamers takes a flight of imaginative fancy into alternative locations. Rather, these sleep-hauntings occur in recognisable locations to the dreamers: in their houses and bedrooms, their gardens, the local police station’s cells, even the bath in one memorable sequence.

While at first it might appear that Wes Craven was not making the most of the dream concept, particularly in comparison to later instalments, the dreams are successful here, not only for how disturbingly Freddy stalks and assaults his prey, but also for what it says about the larger story. Freddy will not allow the children to leave Elm Street, not even in their dreams. Their parents of Elm Street killed him, and so it would be symbolic for Freddy to kill the kids on Elm Street itself, or in the boiler room where he killed previous Elm Street children in (and was burned to a crisp inside). Elm Street functions as the pivot around which all killing resides.

Knowing that enhances the terror of the nightmares, which in themselves are terrifying enough. They are almost like photo negative versions of Elm Street; dark and black-shadowed, as opposed to the polaroid colour of day. The streets are decorated by mist and by the haze of street lamps, bringing the shadows into sharper relief.

Saying all this, Freddy does prove to be able to stretch an ‘elastic reality’ in these dreams—quite literally, as in the moment he stretches his arms out to monstrous, inhuman lengths to scratch the fences. He can turn a mouthpiece of a phone into his own literal mouth, and he can walk through cell bars as if they were air. But all of these fantastical moments are still grounded in the dream-reality of Elm Street locations.

These are nightmares as symbolic of the punishment the children must suffer for the crimes of their parents.

Parental Guidance is Advised

In a way, the parents of Elm Street are more like the pitchfork-and-fire-wielding villagers hunting down the Monster in Universal’s Frankenstein than the sophisticated, middle-class suburbanites they appear to be. Let down by the supposed ‘civility’ of the legal system that is supposed to protect them and give them justice, they regressed to a primaeval, mob mentality, harnessing the elemental power of fire to burn Fred Kreuger to death for their own bloody sense of justice.

The contrast between expectation and the reality of the parents’ past provides a palpable tension. You expect moral outrage in the suburbs—the petty, nagging, trivialities of the neighbourhood ‘Karen’—but not murder (despite what a number of films might tell us). A Nightmare on Elm Street plays into the stereotype of the suburbs: a bland, banal, uniform exterior environment, masking and potentially motivating dark, secret, shameful activities behind the ubiquitous curtains and blinds. The parents of Elm Street display a typical cool, suburban exterior to hide the secret of the violent retribution they committed.

The film takes a judgmental, moralistic view of the actions of the parents. Its conclusion is almost biblical: because of the murderous sin of the parents, their children are doomed to be put to death by the symbol of that sin: the supernaturally returned Fred Krueger. The children have no choice in the matter, nor have they done anything wrong: they are to die because their parents did not consider the consequences or their own responsibilities.

A deleted moment makes the attitude clear, an exchange of dialogue that was filmed and took place in the middle of the basement confession scene between Nancy and her mother, Marge. Nancy asks her mother, “What gave you the right to take the law into your own hands?” There is the law of paper and policemen, and there is the law of morality, of living the ‘correct’ way. The parents of Elm Street, the film posits, have broken both of these laws.

Not only that, but there is an emotional neglect of the children, too, an inability to empathise with them. After Tina’s death, Nancy’s dad, Lieutenant Don Thompson, is only concerned with what Nancy was doing around a ‘delinquent’ like Rod, rather than how upset Nancy is at the death of her best friend. Marge even accuses Nancy of not taking Tina’s murder seriously. Lieutenant Thompson uses his own daughter as bait to draw out and arrest Rod. He even dismissively asks one of his men to watch Nancy after she tells him she knows who the killer is, humouring her rather than trusting her.

So, who is the real enemy? Fred Kreuger or the parents? A Nightmare on Elm Street never diminishes Kreuger’s evil, but it demands you recognise the culpability of the parents without giving them a fair trial. And I say it was time we put the parents in the dock.

Who Can Judge the Traumatised?

The curious thing about A Nightmare on Elm Street is that it never gives the Elm Street parents the benefit of the doubt or any leeway. Indeed, I had never given the parents any leeway until a recent rewatch, but as a parent, I think it is interesting how the film never tries to present the parents’ point of view other than in exposition, nor does it try to see things from their point of view.

Now, to be clear, I cannot and do not justify murder. But it is not too hard to put yourself in the shoes of the Elm Street parents and understand how they came to their act of retribution. They have been let down by the law, the civil way of deciding and executing justice. This ‘civility’ of rules, of ‘doing things by the book’ has led to a situation where a child murderer has been set free because a piece of paper wasn’t signed correctly. But paper burns, and so do men, and with their deaths of their children going unavenged by the law, and with a child murderer still in their town, potentially looking to kill again, a combination of grief, hysteria, disillusionment and fury drove the parents to act for themselves.

I don’t condone it, but I can understand it. As Marge responds to Nancy in that deleted scene, under the accusatory question of how the parents could take the law into their hands, “because he took it into his hands to kill our kids. Glen, Rod, Tina, they all had a brother or sister once. You too, Nancy. You weren’t always an only child.”

It’s interesting that Craven cut this exchange from the final film. I suspect that it’s because Marge’s response dilutes the argument that the film pushes: that the sins of the parents are inherited by the children. It is easier for the film, and makes for a more direct, digestible argument, that the parents have consigned their children to an early death, and that the children will have to clear up their parents’ mess. That’s quite the example of an almost biblical intolerance, which raises the question of Christianity in the film.

The Crucifix Subverted

Not all horror films deal with religious themes, but it is not unknown for Christianity to appear. Hammer’s Dracula series, as with a lot of Dracula movies, shows the titular vampire to be weakened by the sight of a crucifix; The Exorcist is a film-length essay on the concept of Catholic guilt; even the later ‘Elm Street‘ films give Freddy a nun for a mother and see him defeated by holy water.

On the surface, A Nightmare on Elm Street doesn’t play as a Christian tract, outside of the parent/child revenge situation bearing a similarity to the punishment threatened in Exodus 34:7 (and conveniently ignoring Ezekiel 18:20), but there is enough symbology to suggest a reflection of Craven’s distaste of the strict Baptist upbringing he suffered, something he rejected as an adult.

The film never specifically states that God exists, or even how Freddy was resurrected—later films will give ideas, but not here. What Freddy is and how he works—is he a ghost? A demon? A soldier of Satan?—is left to the imagination and to ambiguity. That’s partly because focusing on Freddy as a force of revenge strengthens the theme of the children inheriting the consequences of their parents’ sins. But I think it is also Craven suggesting that there are forces at play here beyond human understanding, and they are not necessarily Christian.

As such, Tina clutches a crucifix as she sleeps, in the hope that she will be protected by the talisman, but it does not stop her from being slaughtered by Krueger. Just before Tina’s death, a crucifix falls off a wall and onto Nancy’s head, as if Craven is poking fun at the characters for expecting the crucifix to protect or save them: ‘Look, this is only going to hurt you.’ It is notable, then, that when Nancy finds a crucifix in one of her visits to Freddy’s boiler room, she does not take it. In fact, it disappears, as if the thing itself and what it symbolises are imaginary.

The only crucifix that seems to have any success in the film is Freddy’s body itself. In the confrontation with Tina that results in her death, Krueger holds his arms out at his side, as if he were making his own body into its own grotesque crucifix, and stretches his arms out to inhuman lengths, either to mock Tina’s beliefs or just as an act of blasphemy in and of itself. As he says, as Tina cries out ‘Oh, God!’ at the sight, “This is God”. He refers to the act of chopping off his own finger, a kind of degradation of power, but in the way he has cast himself as judge, executing the sentence of revenge against those who revile him, Freddy has become here a kind of Old Testament God, one who would recognise the plagues that rained down on Egypt.

That such a God is presented as monstrous by Craven in the figure of Freddy does not seem to be coincidental.

The Final Girl: Virginity Need Not Apply

What to be said of Nancy, then, Freddy’s main antagonist and the Final Girl of A Nightmare on Elm Street?

The ‘Final Girl’ syndrome has been discussed, analysed and evaluated by countless writers over the years. One facet of the syndrome that seems to be agreed upon by a lot of commentators, and not without some fair reasons, is that, whether intentionally by the writers and director or not, the ‘Final Girl’ will tend to be a teenager, and the one person in the film who has not had sex and has remained virginal. This sees the slasher sub-genre then as being inherently conservative, where teenage promiscuity and sex before marriage are punished by murder.

I don’t think Nancy survives, though, because of her virginity. Her boyfriend Glenn, the film implies, is a virgin too, and he gets killed in the bloodiest way possible. And by the law of averages, not all of the kids on Elm Street and environs are going to have had sex. Our heroes here are just a small sample of Elm Street’s child population, and not everyone grows up to be a Rod (some of us grew up more like Eugene in Grease. Who, me? I’m not telling you).

Sex, in fact, seems inconsequential to the film’s major mythology. Freddy is stalking the children due to their sexual activity, but is fulfilling his need to kill children while taking revenge against their parents in the same act. If anyone has real significant sexual drive here, it’s arguably Freddy, if the implication that he was also a paedophile is correct. Tina just wanted the comfort of her friends and a distraction from and placation of her fears. She didn’t want to have to face the problem of Freddy head-on. Yes, she gave in to Rod and slept with him willingly, but this wasn’t the purpose of the sleepover. Rod, if anything, forced his way into the situation.

As for Rod, he panicked at Tina’s death and went into self-preservation mode, hiding away until caught by the law. This ultimately led to his death, as, once stuck in a cell, there was nowhere left to run. Glenn, meanwhile, seems to be ambivalent at best and careless at worst. Even though he seems to react in recognition at Nancy’s description of Freddy, he doesn’t seem to take the situation seriously. He falls asleep both times Nancy needs him to stay awake, and after the second time, he ends up being collected in bloody buckets.

Nancy, on the other hand, survives because she does confront the problem of Freddy directly. She tried to stay awake, consuming endless cups of coffee, even going so far as to hide a percolator in her room. But you cannot outrun sleep. Finally, Nancy understands that, because Freddy is relentless in his desire and his fury, the only way of possibly surviving him is to defeat him, not to run away.

To this end, she researches combat techniques and makeshift weaponry; she sets her house up to be a gigantic booby trap to catch Freddy; she successfully pulls Freddy into the waking world to fight him on her terms and by this world’s physical rules; she even sets Freddy on fire, re-establishing the concept of punishment back onto the monster. It is Nancy’s ability to act, to not be passive, that sets her on the path to survival.

Yet, it is something Glenn says to her, something she internalises and takes to heart, that grants her salvation. Discussing the Balinese way of dreaming, Glenn tells Nancy how they use “dream skills” if they have created a monster in their dreams to “turn their back on it. Take away its energy, and it disappears.” Nancy has been fighting Freddy physically, even in the mental plane, but it is only by being purposely conscious of your mind, by being aware that your mind is creating the dream and thereby giving Freddy power to appear and exist, that you can realise the power to discipline your consciousness and control your own dreams.

It is a concept of hyper-self-awareness, a kind of extreme mindfulness, and it is what finally saves Nancy (ending car-and-mannequin scene aside). By turning her back on Krueger, by being hyper aware of her mind and taking away the power it gives Freddy to exist in her dreams, it eradicates his existence—at least until the sequel. It is this mindfulness, the ability to face the reality of the problem and to confront it, and not her virginity, that makes Nancy the Final Girl of A Nightmare on Elm Street, and perhaps one of the greatest Final Girls of all time.

Final Thoughts

A Nightmare on Elm Street was a major success and was the film that really built New Line Cinema as a studio. Made for a paltry $1.1 million, it reaped a box office return of $57.1 million, making Fred Krueger a household name. A sequel was inevitable, but the birth of a major horror franchise is not the only legacy the film has left behind.

Because of the imagination and creativity the film displayed in its approach to the genre, A Nightmare on Elm Street opened the door for other slasher films to be more creative, less formulaic, and less reliant on copying the Halloween/Friday the 13th formula.

It proved that a film’s main monster could have layers, didn’t have to be a blank slate, and could have a strange charisma. And, for better or worse, it proved a horror film could be taken seriously enough by the mainstream to become a cornerstone of pop culture. Yes, that did dilute the character’s scare factor, but imagine how delicious it would be to have a creature like Freddy Krueger haunting the mainstream now.

I can only dream…

Leave a Reply