The year 1942 was the the symbolic terminal point for the Classic Monster. Universal’s pantheon—the aristocrats in capes and the tragic hulks in bandages—had become safe. They were creatures of the light, their every move choreographed, their makeup kits fully visible to even the most casual observer. They belonged to the theater of the grand gesture. But the world was changing. Real-world horror was no longer found in a distant castle; it was found in the blackout curtains of London and the predatory silence of the Atlantic.

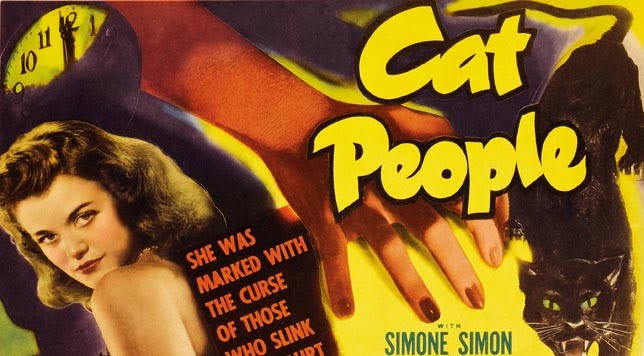

Val Lewton recognized that horror needed to move inward. As the head of RKO’s B-horror unit, Lewton was given a mandate that should have resulted in cinematic garbage: make movies for under $150,000, use titles that sounded like pulp magazines, and don’t go over 75 minutes. Instead, he produced Cat People, a film that didn’t just justify a studio’s gamble—it laid the groundwork for the modern psychological thriller.

The RKO Mandate: Art Through Limitation

To understand Cat People, you must understand the economics of its creation. RKO was bleeding out. Charles Koerner, the head of production, didn’t want art. He wanted product. He handed Lewton a list of titles that had been focus-grouped for maximum prurient interest. Cat People. I Walked with a Zombie. The Leopard Man.

Lewton, a man of profound literary ambition, was horrified. But rather than phone it in, he staged an aesthetic coup. He decided to use these lurid titles as Trojan horses. He would give the studio the Cat People they asked for, but he would strip away the rubber suits and the literalism. He would replace the monster with the mood.

This was the birth of the philosophy: Constraint is the mother of ingenuity. By having no money for elaborate special effects, Lewton and director Jacques Tourneur were forced to rely on the audience’s own neuroses. They realized that the cheapest effect in Hollywood—the shadow—was also the most terrifying.

The Immigrant Dread and the Failure of Reason

At its core, Cat People is an interrogation of the American rationalist dream. Irena Dubrovna (Simone Simon) is a fashion designer from Serbia living in a New York that is obsessed with geometry, blueprints, and common sense. Her apartment is a fortress of Old World iconography, dominated by a statue of King John of Serbia impaling a cat.

Irena is the quintessential other. She carries the weight of ancestral trauma—the belief that she is descended from a tribe of devil-worshippers who transform into panthers when aroused by passion or anger. But notice how the film handles this. It never confirms it. From this perspective, Irena’s curse is an ontological crisis. She is a woman who cannot exist in the modern world because the modern world refuses to acknowledge the reality of her internal landscape.

Oliver Reed (played by Kent Smith), her husband, is the personification of the good sport. He is a man of drafting boards and straight lines. He believes that every problem can be solved with a conversation, a stiff upper lip, and a professional intervention. He is fundamentally decent, and fundamentally useless. He loves Irena, but he loves the idea of a normal wife more. When he realizes she has a spiritual and psychological interior that doesn’t fit into his blueprints, he recoils. He turns to Alice—the girl-at-the-next-desk—because Alice is legible. Alice is safe.

The conflict in Cat People isn’t between a hero and a monster; it’s between Empiricism and The Unknowable. Dr. Judd, the psychiatrist, is the most dangerous element of this triad. He represents the arrogance of the clinical gaze. He believes that by labeling Irena’s fear, he has conquered it. He views her not as a human being, but as a case to be solved and, eventually, a body to be possessed. His treatment is a form of intellectual gaslighting. He dismisses her deep-seated ancestral fears as hallucinations, not because he wants to help her, but because he wants to dominate her.

Stop Demanding the Reveal

Let’s get one thing straight: if you’re the kind of viewer who needs a CGI transformation sequence to feel scared, you’ve been lobotomized by modern cinema. The power of Cat People lies in its calculated omission.

Lewton and Tourneur understood that the human eye is a lying organ. It wants to resolve shapes. It wants to categorize the threat so it can dismiss it. By denying the audience a clear look at the panther, the film forces your brain to fill in the blanks. You aren’t watching a movie; you are hallucinating a nightmare in real-time.

Look at the bus scene. This is the sequence that redefined film editing. Alice is walking alone through the park. The silence is absolute, save for the clicking of her heels. It is an insistent sound that pulses like a heartbeat. The tension builds until it is physically uncomfortable. Your lizard brain is screaming that a predator is inches away. And then—HISS.

A bus pulls into the frame, its air brakes releasing with a sound that perfectly mimics a feline snarl.That is the Lewton Bus. It’s a masterpiece because it’s a jump-scare that mocks the very idea of a jump-scare. It releases the tension with a mundane object, but it leaves the dread intact. It tells the audience: “You were right to be afraid, even if you were wrong about why.” It proves that the fear is already inside you. The movie just provides the trigger. If you think that’s boring, go back to watching guy-in-a-suit sequels. This is psychological warfare.

The Horror of the Pool

If the Bus scene is about the jump, the pool scene is about the total collapse of safety.

Alice, pursued by an unseen force, takes refuge in the basement swimming pool of her apartment building. It is a subterranean, tiled tomb. The only light comes from the reflection of the water on the ceiling—a shimmering, unstable web of light and shadow.

This is where Nicholas Musuraca’s cinematography becomes a character in its own right. He uses low-key lighting not just to save money, but to create a sense of liminality. Alice is in a modern, functional space, yet she has never been more vulnerable. The echoes of the water mask the approach of the predator. When she hears the growl, it is amplified by the tiles, making it omnidirectional.

This is the ultimate expression of the unseen. Whether Irena has physically turned into a cat or she has simply tracked Alice down with a murderous obsession is irrelevant. The dread is the same. The fear isn’t of a panther; it’s of the absence of light. It’s the realization that even in the heart of New York City, you are still a biological organism capable of being hunted.

The Soundscape of the Abyss: Beyond the Bus

We need to discuss the auditory architecture of this film. Lewton’s team utilized sound with a clinical precision that was decades ahead of its time.

Consider the canary sequence. Irena buys a bird, but her presence causes it to die of sheer terror. The frantic fluttering of the bird against its cage is a sonic representation of Irena’s own trapped psyche. Later, when Irena is in the drafting office, the sound of a pencil scratching against paper becomes oppressive.

The most terrifying sound in the film, however, is the silence. In the zoo sequences, the roar of the lions in the background creates a constant primal baseline, but when Irena approaches, the animals go silent. It is a predatory hush. This use of negative space in the soundtrack is what makes Cat People feel so modern. It doesn’t tell you how to feel with a melodramatic score; it forces you to listen for the thing that isn’t there.

Sexuality as a Death Sentence

Let’s be direct: Cat People is a film about the terror of intimacy.

In 1942, Hollywood was governed by the Hays Code, which forbade explicit depictions of sex or perversion. Lewton used this censorship to his advantage. Irena’s curse is a literalization of the fear of sexual awakening. She believes that if she is aroused—if she kisses her husband—she will transform into a beast and kill him.

From any perspective, this isn’t just a cat curse. This is a study in sexual repression. Irena is a woman paralyzed by the expectation of being a normal wife in a society that has no room for her specific trauma.

The character of Alice provides a stark contrast. Alice is the career woman. She is competent, rational, and sexually available in a way that is safe for Oliver. The film creates a triangle where the New Woman (Alice) is pitted against the Atavistic Woman (Irena). The horror isn’t just in the panther; it’s in the way Oliver casually discards Irena the moment her psychological complexity becomes an inconvenience.

Oliver is the true rational monster. He treats Irena like a broken appliance. When she can’t be fixed by Dr. Judd, he simply moves on to Alice. His lack of empathy is the catalyst for the film’s violent conclusion. He didn’t want a partner; he wanted a blueprint that stayed on the page.

The Arrogance of Dr. Judd

Dr. Judd is the villain that I love to hate. He is the predatory intellectual who thinks his degree makes him immune to the darkness.

In the film’s climax, Judd confronts Irena in her apartment. He attempts to kiss her—an act of clinical dominance disguised as a cure. He wants to prove that her fears are mere fantasies. He wants to conquer her myth.

His death is one of the most satisfying paybacks in the genre. He is killed by the very thing he claimed was a delusion. As he dies, he realizes—too late—that his labels and his logic were useless against the power of the other. He mistook his academic theories for the actual boundaries of the world.

He is a warning to all critics and scientists who think they can fully map the human psyche. There are corners of the mind that remain unlit for a reason.

The Technical Revolution

We must bow to the cinematographer, Nicholas Musuraca. If Lewton was the soul and Tourneur was the mind, Musuraca was the eye.

Before Cat People, horror was mostly high-key or expressionistic in a theatrical way. Musuraca introduced a gritty, high-contrast realism that would go on to define Film Noir. The use of single light sources, the crushed blacks, and the framing of characters through bars or shadows—all of this started here.

This wasn’t just an aesthetic choice; it was a necessity of the B-unit. By keeping the sets dark, they could hide the fact that they were reusing old RKO sets. But in doing so, they created a visual language of doom. They proved that the dark wasn’t just a place where monsters lived; it was a psychological state.

When you watch a noir film like Out of the Past (also shot by Musuraca), you are seeing the direct descendant of the RKO horror cycle. The Femme Fatale is just a Cat Person without the claws. She is a woman whose very existence is a threat to the rational, male-dominated world.

Final Thoughts

I’m tired of hearing that old movies aren’t scary. If you find Cat People boring, it’s because your imagination has been cauterized. You’ve been spoon-fed until you’ve lost the ability to hunt for the subtext.

Cat People is a confrontation. It asks you: What part of yourself are you terrified to meet in the dark? Val Lewton was the architect of the unseen. He took the cold, harsh reality of the human condition and projected it onto a screen using nothing but a few lights and a lot of nerve. He moved the genre away from the gothic fantasies of the 1930s and into the psychological reality of the modern era. Without this film, there is no Psycho. There is no Alien. There is no The Witch.

Cat People is the moment horror grew up. It stopped being a fairy tale and started being an interrogation. It proved that the most terrifying thing in the world is the feeling that we are being watched by something we refuse to believe in.

Val Lewton didn’t just make a movie in 1942. He opened a door to the abyss. And once you’ve looked into that abyss—once you’ve heard the cat-scream in the New York night—there is no going back to the safety of the light.

Cat People remains a masterclass because it respects the audience enough to let them be afraid. It doesn’t hold your hand. It doesn’t show you the monster. It simply turns out the lights and asks: “Do you hear that?”

Leave a Reply