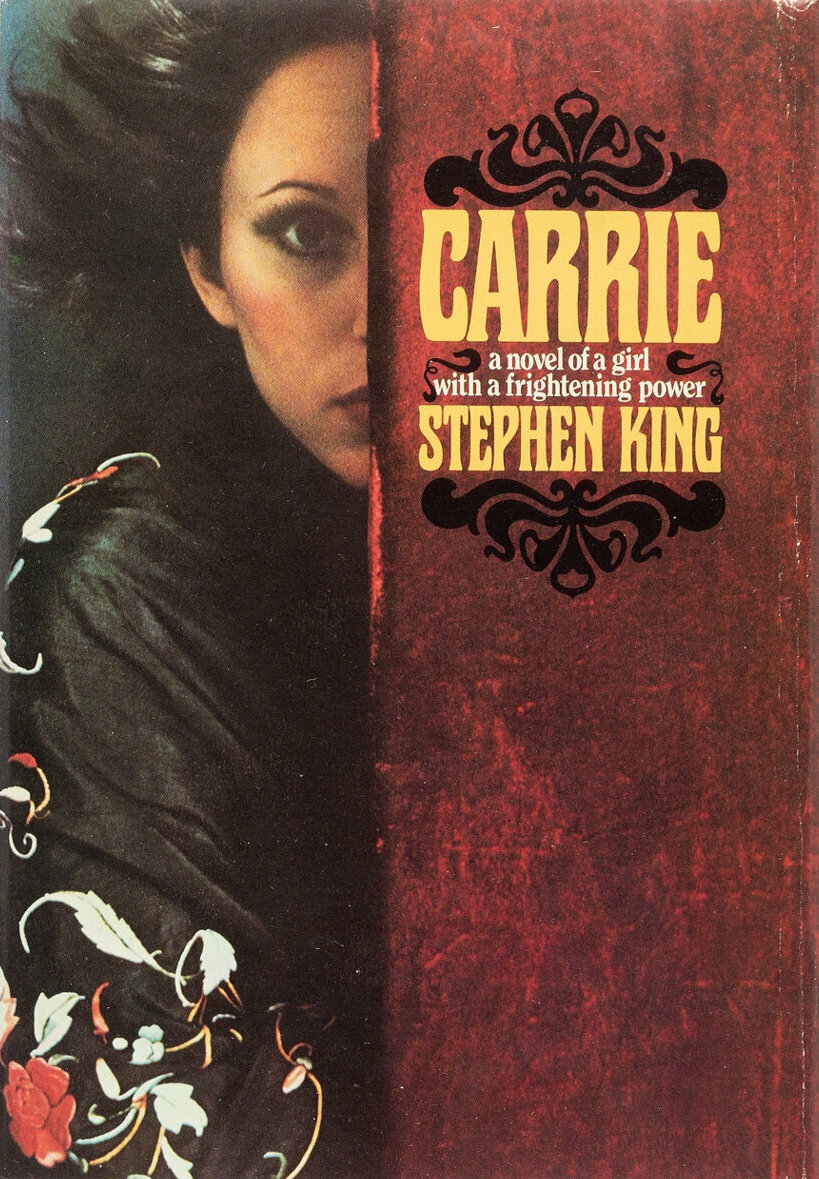

Recently I re-read Stephen King’s debut novel Carrie. I hadn’t read it since high school and reading it again as an adult gave me a whole new understanding of the book. Not just as a profound empathetic statement, not just as a piece of social commentary, but also as a formative text for King as an artist and a definitive example of ’70s horror. While Brian DePalma’s film adaptation of Carrie is iconic, it only skims the surface, strictly delivering the plot of King’s novel, whereas the book itself is actually about something quite different, and also much larger in scope despite its short length.

When considering ’70s horror, we often think about stories which take the superstitious genre devices of decades past and explore them with a more grounded approach, looking at the kinds of things William Castle may have shocked you with in earlier years through a decidedly modern and scientific lens. Castle even helped kick things off himself with 1968’s Rosemary’s Baby, which trades in Roger Corman’s Technicolor Occultism for the verisimilitude of New York City. The Exorcist is perhaps the definitive example, which takes a tale of priests and demonic possession and juxtaposes that spirituality with the cold determination of the medical and scientific process. Another classic example is Philip Kaufman’s 1978 remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Invasion takes the pulp ‘50s classic and looks at it through a more overtly scientific examination of theoretical alien life, how it might travel and gestate and view the world. In addition, Kaufman examines the rise of pop psychology, questioning the value of the enterprise by asking if it actually helps people understand themselves and the world around them or just utilizes the language of the field to condition people to accept a certain state of affairs.

We see examples of this even outside the United States. Konstantin Yershov’s 1967 film Viy, produced in the Soviet Union, takes Nikolai Gogol’s story about the titular King of the Monsters and looks at it through the lens of superstition and myth. The film’s opening narration openly dismisses the validity of demons as something which we accept exist in the modern world, pitching the film as a fun historical study of how people thought back then.

On the small screen, Dan Curtis and David Chase kick-started the “paranormal procedural” exemplified by shows like The X-Files during this time as well, with Kolchak: The Night Stalker, where paranormal and supernatural events are being investigated seriously by a veteran journalist with a dogged approach.

Carrie is very much part of this tradition. It isn’t just a story about a girl who wreaks havoc at the prom, it’s about deep-seated issues with American society. King explores our social structures, how they create toxicity both at home and in public, how that toxicity goes unexamined and festers, and also how American society at large interacts with the awareness of world-shaking revelations, in this case psychic phenomena. Carrie is in fact an epistolary novel, cutting back and forth between the story proper and outside newspaper articles, studies, and journals, which document how the United States wrestles with the outcome of the event.

In King’s novel, the story becomes so much larger than just Carrie’s experience. King’s propensity to jump sometimes years ahead with the external documents, making vague references to events yet to be depicted not only creates tension, it actually turns the book into a powerful, poignant, at times enraging experience. King emphasizes the juxtaposition between Carrie’s personal experience and the way the wider world looks at her, both before and after the incident on Prom Night.

To quote Shakespeare:

“The evil that men do lives after them; The good is oft interred with their bones.”

This really gets at one of the book’s major themes: How society turns people into monsters both before and after they die. Carrie is abused from a very young age by her mother through the lens of Christian fundamentalism, which then translates into abuse at the hands of her peers in the brutal public school system. Carrie is ruthlessly bullied for being strange and different, and this creates in her a rage which we get to experience first-hand. King communicates the depth of her unhappiness with painful clarity. Despite this, there remains a beauty and whimsy to Carrie, a keen sense of humor which rises to the surface as Sue and Tommy work to bring the girl out of her shell.

In the end of the book, Carrie does more than just attack her fellow promgoers. Her rampage spreads across the whole town of Chamberlain, Maine. She takes her revenge on the entire community which essentially enabled her abuse for 16 years. Very few people attempted to defend her from her mother or peers, and those who did were quickly cowed. Her actions across Chamberlain on Prom Night result in the deaths of hundreds of people. It’s a stark and powerful metaphor for how little issues become big issues. How the further you pull the rubber band, the more it hurts when it snaps back.

Ironically, this action is what it took for the world to finally notice Carrie White. All most people really know about her is the violence and destruction she finally wrought, and so as a result all her inner turmoil, all her better qualities are disregarded. To heighten the irony, one of the very few who defends her in retrospect is Sue Snell, one of her initial bullies. This is because Carrie’s power, in the final moments of her life, as she lies bleeding after a knife attack at the hands of her own mother, facilitates true psychic connection between the two. Sue and Carrie finally come to understand each other. Carrie’s rage was exacerbated by the misunderstanding that the events leading up to Prom Night were an elaborate prank on Sue and Tommy’s part. Carrie now comes to understand Sue truly was sorry for her part in the incident in the shower. Sue comes to understand all of Carrie’s hurt and anger and how her whole miserable life was essentially one big trick played on her in order to make her unhappy. But for the world at large, Carrie is abstracted by the events which led up to her death, and whatever Sue knows or believes about her is rendered meaningless. Strangers are searching for meaning and discourse now, and Carrie’s truth becomes lost in the study of what happened.

Carrie, Sue, and even Tommy’s beliefs, thoughts, motivations, and character become subject to interpretation from various researchers, journalists, and thinkers. The American scientific and media establishments principally choose to impugn and debase Carrie and Tommy after their deaths, and Sue now as an adult. Through this, King explores how the United States tends to atomize everything instead of thinking about how these incidents are produced on a social or structural level. We only look at the individual people involved and seek to issue moral judgment. This results in the structures of science failing to reckon with the true potential concern Carrie’s power represents.

In addition to Carrie serving as part of the tradition of ‘70s horror, seeing the supernatural through the lens of science and the modern age, Stephen King is also giving us the blueprint for himself as an artist. For starters, Carrie introduces us to his trademark forthright prose, which vacillates between the rough-hewn and the elliptically poetic, punctuated with a strong ear for dialogue. King’s reputation for understanding the soul of the American conversation begins here. What also immediately impresses here is how, despite the novel’s conceptual brilliance, it’s also very accessible. King strikes a difficult balance between the adventurous and the entertaining. Like much of King’s work, Carrie is an easy read with a transgressive streak. You never know when King will punch you in the gut.

In addition to the visceral nature of King’s prose, we see the beginnings of his focus on his characters’ reactionary feelings and intrusive thoughts. While this will become a major element of his style, it also ties quite well into Carrie’s psychic themes.

Another of King’s major themes is his skeptical perspective on religion, especially American Christian fundamentalism. We see this in Carrie right from the jump, where Christian fundamentalism creates problems where none exist, issues non-working solutions to those problems, then Christian fundamentalists take credit for the tragic conclusions of the problems their worldview directly created. An anonymous epitaph is left for Carrie on her mother’s property after her death, reading “Carrie White burns in Hell. Jesus never fails.” This is one of the most grim and tragically poignant things I’ve read in a novel. King at his best reaches a Kurt Vonnegut level of devastating simplicity.

More of King’s themes can be traced back to Carrie. A core theme will be his penchant for picking up the stone of ‘50s Americana to look at the insects teeming underneath. This begins here with one of the antagonists, Billy Nolan, a greaser out of time with a car that he’s obsessed with to the point of infatuation, presaging Christine. Psychic power will be something he returns to in the future, with The Shining, The Dead Zone, and more.

Beneath all this, Carrie’s heart beats with the pain of the personal. There’s both an unflinching and sympathetic quality to King’s examination of bullying and abuse. King was working as a high school teacher at the time of Carrie’s writing, and sure enough the book takes place largely at a high school, with a prominent character who is a young teacher. Rita Desjardin may well serve as King’s viewpoint character in the world of teenagers, a way to express his feelings on things he may have felt or seen as a teacher.

In 2026 we still have a tendency to sweep things under the rug and not fix our problems in decisive fashion. Because of this Carrie, as a novel and as a character, still resonates today. Her pain, her potential, and her hope, dashed upon the rocks of an uncaring world, speaks as clearly today as it did a half-century ago. The uniquely ’70s mélange of superstition and science, King’s deceptively powerful prose, his eternally relevant look at bullying and how the human propensity to form in and out groups can create contradictions within the individualist American society, all remain powerful. We could still stand to learn Carrie’s lessons, and thankfully we still have time.

Leave a Reply