There are films you love because they’re good.

There are films you love because they’re important.

And then there are films you love because something in them is fundamentally wrong, and it presses a button you don’t fully understand.

Werewolf in a Girls’ Dormitory is that third kind of film.

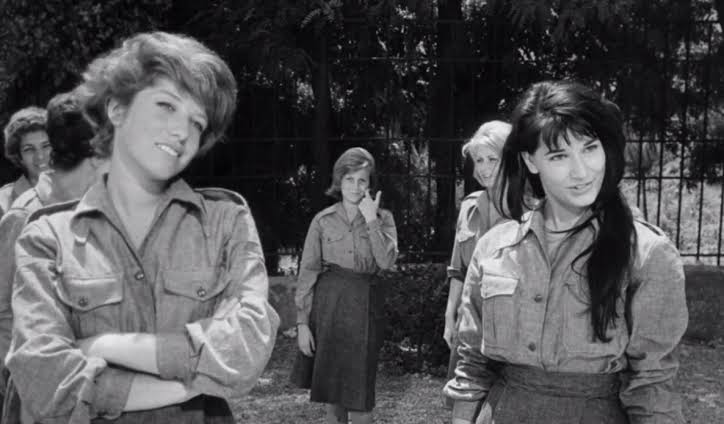

This is a 1961 Italian horror-mystery, originally released as Lycanthropus, directed by Paolo Heusch and written by Ernesto Gastaldi — and on paper, it should be a straightforward genre exercise. Black-and-white. Boarding school. Murders. A suspected werewolf. Job done.

Except nothing about this film behaves the way it’s supposed to.

It is sleazy without being explicit, gothic without being romantic, violent without being thrilling, and a werewolf film that seems faintly embarrassed about the idea of werewolves at all. It’s confused, morally queasy, structurally unsound, and constantly threatening to fall apart.

And I love it.

I genuinely do.

And I still can’t fully explain why.

The Title Lies to You Immediately

Let’s deal with the first betrayal up front.

Yes — there is a werewolf element in this film. There is a wolf-like figure. There is lycanthropy in the plot.

But if you’re coming in expecting anything resembling traditional werewolf cinema — transformations, folklore, moonlit tragedy — you’re going to be disappointed almost immediately.

The werewolf angle in Werewolf in a Girls’ Dormitory functions less like a myth and more like a narrative excuse. It’s part psychological, part symbolic, part “we needed something spooky to sell this internationally.”

This is not The Wolf Man.

It’s not I Was a Teenage Werewolf.

Shit. It’s not even Teenwolf.

It’s a murder mystery in a boarding school that occasionally remembers it promised you a monster.

And honestly? That mismatch is half the fun.

Murder, Institutions, and Bad Vibes

The film is set in a girls’ boarding school / reformatory — already an uncomfortable location for a horror film, especially one made in 1961. Young women are being murdered. Their bodies turn up strangled, broken, discarded.

Naturally, suspicion falls on the authority figures.

Enter Dr. Julian Olcott, a new science teacher with a shady past involving a mental institution, a dead wife, and rumours of lycanthropy. He’s quiet. Brooding. Constantly framed like the camera doesn’t trust him — which, to be fair, it shouldn’t.

Around him orbit headmistresses, doctors, inspectors, and staff, all behaving like they’re hiding something — because in Euro-horror, they always are.

The film wants to be a whodunit.

It wants to be psychological horror.

It wants to be gothic tragedy.

And it also wants to be a werewolf movie.

It doesn’t know how to balance any of this.

Which is exactly why it’s fascinating.

Everyone Is in a Different Film (And Somehow That Works)

The performances are all over the place.

Barbara Lass plays the headmistress with stern gothic seriousness, like she wandered in from a Hammer knock-off that never got made. Carl Schell plays Olcott with repressed intensity, all guilt and shadow. Luciano Pigozzi, showing up as a creepy doctor, does what he always does: sweats, stares, and radiates menace like a human oil spill.

The students drift between terror, boredom, and mild hysteria, sometimes within the same scene.

No one seems to agree on tone.

No one seems to agree on genre.

No one seems to agree on what kind of film they’re in.

And yet — bizarrely — it never tips fully into parody.

Instead, it creates a dreamlike disconnect, where everything feels slightly unreal. Not stylised. Just off. Like you’re watching a nightmare someone half-remembers and can’t quite explain.

Sleaze Without the Payoff

This film is sleazy.

The camera lingers. The setting is voyeuristic by design. Authority figures leer. Power dynamics are gross. There’s an undercurrent of sexual repression and institutional rot that never really leaves the frame. But what’s strange is how restrained it is.

For a film set in a girls’ dormitory, it’s weirdly hesitant to go full exploitation. There’s no nudity. The violence is suggested more than shown. The sleaze is atmospheric rather than explicit.

This gives the whole thing a queasy edge. It’s not reveling in filth — it’s soaked in repression, and repression is always more unsettling. It feels like a film that wants to be nastier than it’s allowed to be, which creates tension it doesn’t know how to release.

Symbol, Excuse, Red Herring

Yes — the werewolf exists in the story. But the film treats lycanthropy less as a supernatural curse and more as a psychological condition, tangled up with trauma, guilt, and inherited madness. The explanation is vague, pseudo-scientific, and emotionally driven rather than mythic.

If you’re a folklore purist, you’ll hate this.

If you’re watching it as a warped gothic melodrama about identity and repression, it suddenly makes a bit more sense. The werewolf isn’t really the point. The idea of monstrosity is.

Again: does the film explore this well?

Absolutely not.

But it gestures toward something darker than your average cheap horror of the

Cold, Clinical, Uncomfortable

Shot in black and white, the film benefits enormously from its visuals. The boarding school feels cold. Institutional. Hostile. Corridors stretch on forever. Bedrooms feel unsafe rather than intimate. Classrooms feel oppressive.The cinematography does a lot of heavy lifting, giving the film an atmosphere it doesn’t always earn through writing or performance.

The music, on the other hand, is melodramatic to the point of absurdity. Swelling when it shouldn’t. Undercutting tension instead of building it. But somehow, that excess adds to the dream determine.

This is not a polished film.

It’s a damaged one.

Why It’s Utter Trash

Let’s be honest.

This film is trash because:

The title oversells the werewolf angle

The plot wobbles and contradicts itself

The tone is wildly inconsistent

The sleaze is uncomfortable rather than fun

The performances clash instead of complement

The mystery isn’t especially clever

It fails as a straight horror film.

It fails as a proper whodunit.

It barely qualifies as a satisfying monster movie.

If you watched this cold and bounced off it, I wouldn’t blame you for a second.

So Why the Hell Do I Love It?

Because it’s sincere.

Not in a wholesome way — in a dangerous, confused, half-articulate way.

This film takes itself seriously. It doesn’t wink. It doesn’t apologise. It doesn’t try to be camp. It genuinely thinks it’s doing something meaningful, even when it has no idea what that something is. That sincerity, combined with its sleaze and structural failure, gives it a personality most competent films lack.

Werewolf in a Girls’ Dormitory feels like a film that slipped through the cracks. A cursed artefact from a time when genre cinema was still figuring out how much it could get away with.It’s not good. But it’s alive.

I can’t justify it, and I won’t try. Werewolf in a Girls’ Dormitory is a bad film. It’s tasteless. It’s uneven. It’s misleading. It’s morally dubious. But it’s also atmospheric, unsettling, and deeply strange in a way that sticks with you long after better films fade away.

I don’t love it because it works.

I love it because it doesn’t.

Because sometimes the films that fail hardest are the ones that leave the deepest scars.

And I’ve always had a soft spot for scars…

Leave a Reply