Army of Darkness remains one of the most anomalous productions in the history of studio-funded cinema. It represents the precise moment where the garage-band ingenuity of Sam Raimi and Rob Tapert collided with the $11 million resources of Universal Pictures and Dino De Laurentiis. The result was not a polished Hollywood product, but a massive expansion of a DIY ethos—a film that used the budget of an epic to fund the madness of an underground horror flick.

This isn’t just a sequel; it is an experiment in cinematic maximalism. It utilizes almost every form of special effect known to the 20th century—stop-motion, go-motion, animatronics, prosthetic makeup, forced perspective, matte paintings, and early digital compositing. To give this movie the respect it deserves, we must move beyond the boomstick quotes and look at the structural and mechanical brilliance of how this chaos was constructed.

Constructing Castle Kandar

One of the primary drivers of Army of Darkness weight is its physical environment. Rather than relying on European locations or minimalist backlot fakery, the production built massive exterior sections of Castle Kandar on ranch land near Vasquez Rocks in Acton, California. The desert landscape provided scale, but the fortress itself was largely constructed from scratch—battlements, towers, siege ramps, and defensive walls designed to be climbed, smashed, and set ablaze.

Production designer Anton Tremblay created a structure that blended medieval texture with Raimi’s exaggerated geometry. The lines are slightly too sharp, the towers slightly too jagged—storybook architecture pushed toward comic-book aggression. Large practical sections allowed Raimi’s camera to move laterally and kinetically in a way the cramped Tennessee cabin of The Evil Dead never permitted.

The scale, however, came at a cost. High winds and dust storms regularly interfered with shooting. The castle wasn’t a seamless 360-degree structure, but the exterior sections were expansive enough to create the illusion of totality. When stunt performers scrambled across walls during the siege, they were climbing real structures under harsh desert conditions. The dust in the air isn’t digital embellishment—it’s the California desert whipped into motion by industrial fans and the environment itself. The result is a tactile grime that grounds even the film’s broadest slapstick in physical resistance.

The Harryhausen Lineage: Stop-Motion Logistics

The KNB Factor: Prosthetic Evolution

Compositing the Impossible: The Introvision Process

One of the film’s more technically sophisticated tools was Introvision, a front-projection compositing system that allowed actors to be integrated with miniatures and matte elements in-camera. Unlike traditional blue-screen techniques, Introvision reduced edge spill and allowed performers to interact more convincingly with projected environments.

Introvision was used in select composite shots throughout the film, particularly where large-scale medieval landscapes or impossible spatial relationships were required. It helped merge live action with miniatures and matte paintings without the floating look common in early 1990s chroma key work.

The windmill sequence—where Ash confronts the Little Ashes—relied more heavily on forced perspective, split-screen compositing, mechanical rigs, and miniature elements than solely on Introvision. The effect is deliberately chaotic: fractured spatial logic mirroring Ash’s unraveling sanity. Campbell’s performance had to hit precise marks against elements that would be added or layered later, blending vaudevillian timing with mathematical precision.

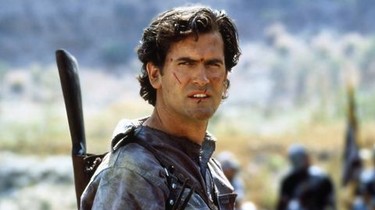

The Proletarian Hero: Ash as the Everyman Toolbelt

To understand the narrative weight of the film, we have to look at Ash not as a chosen one, but as an industrial laborer. Ash’s power doesn’t come from ancient prophecy; it comes from his knowledge of retail logistics and basic mechanics.

The chemistry sequence is the film’s ideological center. Ash uses a 10th-grade science textbook to manufacture gunpowder and a steam-powered Deathmobile. This is a celebration of human ingenuity over supernatural force. Ash doesn’t pray for a miracle; he builds one. He turns the 1973 Oldsmobile Delta 88 into a siege engine.

This subversion of the fantasy genre is what gives the film its enduring cult status. It is the story of a man who is fundamentally lazy and arrogant, yet manages to save the world through brute-force engineering. His mechanical hand, built from a gauntlet and some clockwork springs, is the ultimate symbol of this: a jagged, functional piece of junk that becomes a legendary weapon. It rejects the noble knight archetype, replacing the sword with a chainsaw and the horse with a rusted-out Chevy. Ash is the the hero of the medieval world that they didn’t know they needed—direct, confrontational, and utterly unimpressed by the supernatural.

Oh, and let’s not forget:

“Alright you Primitive Screwheads, listen up! You see this? This… is my BOOMSTICK! The twelve-gauge double-barreled Remington. S-Mart’s top of the line… Shop smart. Shop S-Mart. You got that?”

Which has nothing to do with anything I’ve been talking about, but it’s just too fucking cool to leave out.

The Sound of the Boomstick: Audio Engineering the Apocalypse

The auditory landscape of Army of Darkness is just as brilliant as the visuals. The sound design had to bridge the gap between the clanking of medieval armor and the roar of a 20th-century internal combustion engine.

The Boomstick has a sound profile that is intentionally exaggerated. It doesn’t just bang; it echoes with a metallic, thunderous authority. This auditory weight is vital for selling the anachronism. When Ash fires the gun in the castle, the sound is desegregated from the period environment—it sounds like a piece of the future tearing through the past.

Similarly, the vocalizations of the Deadites create a sense of inhuman aggression. The rhythm of the scream is a key part of Raimi’s directorial style. The soundscape is an industrial symphony of chaos, including squelching mud, clanking bones, and the high-pitched whine of a chainsaw. It is a wall of noise that reinforces the horror of the siege.

The Duel of the Endings: Ambition vs. Satisfaction

The debate between the two endings of the film is essentially a debate about the film’s identity as a work of genre fiction. I mean, they’re both perfect, so stop fucking moaning, but that’s just my opinion.

The S-Mart Ending (Theatrical): This is the crowd-pleaser. It brings Ash back to his own time and allows him to be the hero he thinks he is. It’s a high-energy, action-packed conclusion that leaves the door open for future adventures. It reinforces the idea that Ash is a survivor who has finally found his groove. It pokes fun at the epic by reducing it to a story told in a discount store.

The Post-Apocalyptic Ending (Director’s Cut): This is the darker, more Evil Dead conclusion. Ash drinks too much of the sleeping potion and wakes up 100 years too late, standing in the ruins of a destroyed London. It’s a bleak, ironic twist that fits the franchise’s history of the hero always loses.”

The existence of both endings shows the struggle the production had with balancing its tone. Was this a heroic epic or a cosmic tragedy? By having both, the film remains a fascinating object of study for how a story’s meaning can be completely altered by its final three minutes.

The Visual Tone

The cinematography by Bill Pope (who would go on to shoot The Matrix) is instrumental in giving Army of Darkness its style. Pope used a color palette that moved away from the neon-soaked 80s into a more desaturated, earth-toned 90s aesthetic.

The use of high-contrast lighting in the graveyard sequence—where Ash faces the flying books—is a direct nod to the German Expressionist roots of horror. The shadows are long, the mist is thick, and the depth of field is used to create a sense of claustrophobia even in an open space. This visual language ensures that the film never feels cheap or plastic. It has a cinematic gravity that grounds the slapstick in a world that feels dangerous. Pope’s work praises the practical grit of the set, using light to emphasize the textures of the stone and the rot of the Deadite skin.

S-Mart and the Working Class Hero

We must address the cultural significance of the S-Mart framing. Ash isn’t a scientist, a soldier, or a priest. He is a retail clerk. His mastery over the medieval world is a mastery of the everyman.

The film plays like a rallying cry for the working class. It suggests that the skills required to survive the service industry—patience, multitasking, dealing with monstrous customers—are the same skills required to lead an army. When Ash says “Shop smart, shop S-Mart,” he isn’t just delivering a catchphrase; he is asserting the dominance of the modern consumerist world over the primitive past. It is a fantastic take on the American dream. Ash’s soul is fueled not by noble conviction, but by a desperate desire to get back to his 9-to-5 life.

Final Thoughts

Army of Darkness is a miracle of 90s production. It is a film that stands at the crossroads of cinematic history, looking back at the dirty grit of 70s horror and forward to the epic scale of modern fantasy. It remains a foundational text for anyone interested in the technical reality of genre filmmaking.

It praises the practical effects artist, the stop-motion animator, and the prosthetic designer. It is a celebration of what can be achieved when you have a chainsaw, a chemistry book, and enough arrogance to believe you can take on the legions of the dead. It is the definitive Cult Epic, a film that rewards repeated viewings not just for its jokes, but for the incredible technical craft on display in every frame. It is a masterclass in chaos, and three decades later, its boomstick still echoes through the halls of cinema as an uncompromising cry of resistance.

Leave a Reply