Category: Film

-

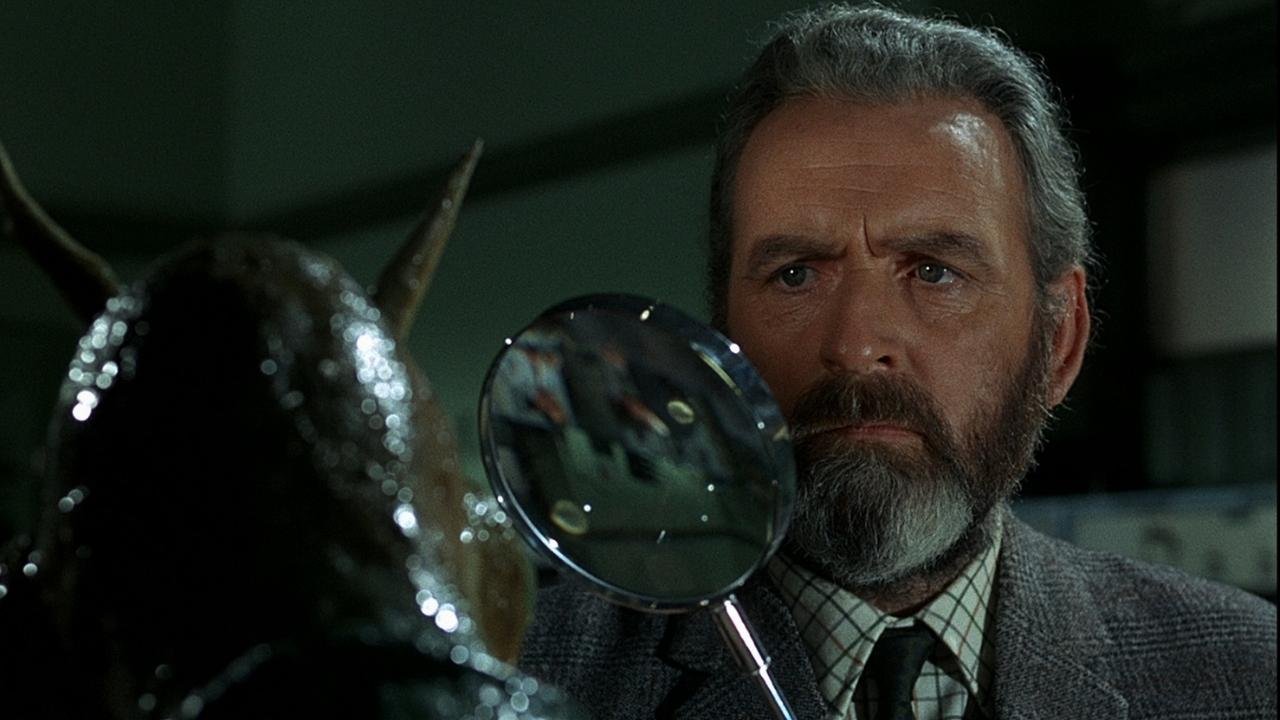

The Undertaker (1988… ish) opens the only way a certain kind of late-80s horror film knows how: with a woman in immediate danger, a road that looks like it hasn’t seen a living soul since Nixon resigned, and dialogue so aggressively stupid it feels like it’s daring you to turn the film off What’s this?…

-

Silent Hill 2 is known among survival-horror fans as a near-perfect entry in the genre. As a psychological horror game, it touches upon serious and mature themes, many that even today most game developers wouldn’t dare address. The game speaks of euthanasia, sexual assault, frustration, guilt, murder, and death. Yet it also deals with themes…

-

Hammer’s Dracula Has Risen from the Grave arrives not as a resurrection, but as an accusation. This is not the aristocratic seducer of Horror of Dracula, nor the vengeful revenant of Prince of Darkness. This Dracula is something more corrosive and more disturbing: a consequence. A curse summoned not by ritual, but by guilt. A…

-

By 1968, Hammer Films was standing on unstable ground. The Gothic cathedral they had spent a decade building—brick by blood-soaked brick—was beginning to crack. The world was changing faster than the studio could repaint its castle walls. Youth culture had turned feral. Authority was suspect. Faith was eroding. Horror itself was mutating into something colder,…

-

By late 1967, the Gothic castle was starting to feel a bit too safe. The shadows of Transylvania were familiar, almost comforting; they belonged to the world of velvet, candlelight, and ancient, predictable curses. To truly terrify an audience staring down the barrel of the Space Age, Hammer had to dig deeper—literally. They had to…

-

By 1967, Hammer’s Gothic cathedral was no longer echoing with hymns. The incense had burned low. The blood on the altar had dried into habit. What once felt transgressive, lush, and sacramental was now being gnawed away by a harsher, less forgiving reality. The world had changed, and Hammer—slowly, reluctantly—was beginning to understand that it…

-

By 1967, the Hammer Frankenstein cycle stood at its most philosophical precipice. Following the commercial necessities of The Evil of Frankenstein (1964), the studio and, crucially, Terence Fisher and Peter Cushing, needed to return the series to its roots: not in the spectacle of electricity and muscle, but in the harrowing inquiry into the nature…

-

By 1966, the Gothic heart of Hammer Films was due for a massive, necessary shock. Following the commercial necessity of the psychological thrillers (The Nanny, Hysteria) and the (unfairly called) misstep of a sequel like The Brides of Dracula (1960)—which dared to feature a world without the Count—the studio was compelled to confront the simple,…

-

By 1965, the Gothic machinery of Hammer Films, which had once felt like a bold revolutionary engine, now risked becoming a repetitive ritual. Audiences, glutted on blood and capes, were demanding a different kind of terror—one closer to home, stripped of historical distance and supernatural alibis. The genre had been redefined by Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho…

-

Released into the crowded horror landscape of the early 1970s, the original Black Christmas was a signal of what was to come, the subgenre that would dominate the next two decades: the slasher. Black Christmas helped codify many familiar tropes that would be used for years (and are still used today), but its treatment…