Step right up, boils and ghouls! Adjust your 3D glasses, ignore the smell of stale popcorn and damp sawdust, and prepare to witness the ultimate forbidden fruit of Pre-Code Hollywood. We aren’t talking about some guy in a rubber suit or a puppet with a bad attitude. No, we are diving headfirst into the murky, mud-soaked trenches of 1932’s Freaks.

If you thought the Necronomicon caused a stir in a Michigan cabin, imagine the chaos this flick caused in the swanky boardrooms of MGM. This is the movie that didn’t just break the rules; it took the rulebook, doused it in kerosene, and tossed it into a pit of rattlesnakes. It’s the grandfather of the macabre, a film so confrontational that it severely damaged the career of its creator, the legendary Tod Browning.

So, grab your favorite bearded lady, and a tankard of Gooble-Gobble punch, because we’re going deep into the madness, the controversy, and the beautiful, twisted heart of the greatest sideshow nightmare ever captured on celluloid.

The Barker Who Became a Director

To understand Freaks, you have to understand the man holding the megaphone. Tod Browning wasn’t your typical Hollywood auteur who studied Shakespeare and drank tea with starlets. Browning was a fugitive from normalcy. At sixteen, he ran away from his well-to-do family in Louisville to join the circus. He didn’t just watch the show; he lived it. He was a barker, a contortionist, and—get this for a B-movie plot—he even had an act where he was buried alive as The Living Corpse.

By the time he hit Hollywood, he brought that carny grit with him. After collaborating with Lon Chaney on films like The Unknown and making Universal a fortune with Dracula (1931), Browning was the king of the creepy. But MGM—the prestige studio of the era—wanted their own piece of the horror pie. MGM reportedly encouraged Browning to develop another macabre property following the success of Dracula. Browning smiled, reached into his trunk of carny memories, and said, “Hold my beer.”

He didn’t want actors in heavy prosthetics. He didn’t want Lon Chaney Jr. in a hairy suit. He wanted the real deal. He recruited the elite of the international sideshow circuit. He brought in the performers who were the rock stars of the midway—people who lived their lives in the fringe, making a living off the gaze of the normals.

MGM had no idea what they were in for. The studio lot became a literal circus. Studio lore claims that even established writers and actors were so unsettled by sharing the commissary with the cast of Freaks that they complained to the brass. The normals were terrified. The freaks were just having lunch. The lines were already being drawn.

The Cast—A Gallery of Living Legends

In any other movie, these performers would be relegated to a background gag. In Browning’s world, they are the protagonists, the antagonists, and the moral compass of the entire story. Let’s look at the roster of this 1930s Monster Squad:

The Hilton Sisters (Daisy and Violet)

Conjoined twins who were massive celebrities in the 30s. In the film, they are depicted with a sense of mundane reality that is staggering for the time. They have separate love lives, separate personalities, and a shared biology that Browning treats with zero sensationalism and 100% human empathy. It’s a masterclass in normalizing the abnormal.

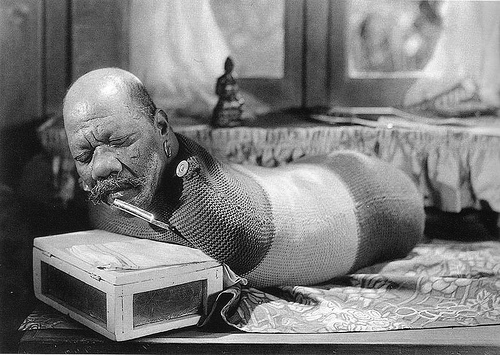

Prince Randian (The Living Torso)

Born without arms or legs, Randian is the ultimate how did they do that? performer. In one of the film’s most famous sequences, he rolls a cigarette, strikes a match, and lights up using only his mouth. It’s not just a trick; it’s a middle finger to anyone who thinks different means incapable. He’s the epitome of the cool, calm, and collected survivor.

Johnny Eck (The Half-Boy)

Eck was born with a truncated torso, but he moved with striking agility and confidence. Watching him walk on his hands is like watching a glitch in the Matrix. He’s charismatic, handsome, and arguably the most normal guy in the whole camp.

Schlitzie and the Pinheads

Schlitzie, born with microcephaly, is the soul of the movie. With a perpetual grin and a child-like wonder, Schlitzie represents the innocence that the normal villains are about to trample. Every time Schlitzie is on screen, you aren’t looking at a freak; you’re looking at a human being who is genuinely happy to be there

The Plot—A Tale of Two Monsters

The story is as old as time, or at least as old as a noir thriller. Hans (Harry Earles), a little person with a heart of gold and a massive inheritance, falls for the normal trapeze artist, Cleopatra (Olga Baclanova).

Now, Cleopatra is the real monster of this flick. She’s tall, blonde, and beautiful, but inside, she’s got a heart like a rotted cabbage. She’s in cahoots with the circus strongman, Hercules (Henry Victor). Together, they hatch a plan: Cleopatra will marry Hans, poison him slowly, take his money, and run off with her muscle-bound boy toy.

It’s a classic grift. But Cleopatra makes one fatal mistake. She underestimates the community. She thinks these performers are just things to be used and discarded. She doesn’t realize that in the world of the circus, if you mess with one, you mess with the whole family.

The Banquet—Gooble-Gobble, One of Us!

If there is a moment in Freaks that stands out as a watershed piece of film making, it’s the wedding banquet. This is the centerpiece of the film, a fever dream of celebration and tension.

The circus performers have gathered to welcome Cleopatra into their inner circle. They pass around a massive loving cup of wine. They begin the chant that has echoed through horror history:

“One of us! One of us! Gooble-gobble, gooble-gobble!”

It’s supposed to be an initiation of love and solidarity. But Cleopatra, fueled by champagne and arrogance, loses it. She screams in their faces, calls them filthy, slimy freaks, and mocks Hans in front of his friends. She shows her cards way too early. The music stops. The smiles vanish.

The normals have declared war. And the freaks? They’ve just accepted the challenge.

The Third Act—The Mud, the Knives, and the Night

Buckle up, because the final twenty minutes of Freaks is where Browning goes full-blown proto-slasher. It’s a rainy night on the road. The circus wagons are bogged down in the mud. The lightning is flashing (classic B-movie atmosphere, baby!), and the tension is thick enough to cut with a machete.

Cleopatra and Hercules think they are in control.

They are wrong.

Out of the shadows, from under the wagons, and through the tall grass, the performers begin to emerge. But they aren’t the smiling, friendly people we saw earlier. They are silent, relentless, and armed to the teeth.

The cinematography here is pure nightmare fuel. We see the performers crawling through the muck. Because they move differently than normals, their approach is uncanny and terrifying. Johnny Eck, Prince Randian with a knife in his teeth, the conjoined twins—they are all part of a collective, vengeful force.

The normals are hunted like animals. Hercules meets a fate that was largely edited out (more on that later), and Cleopatra? Well, Cleopatra gets a makeover that makes the Deadites look like they went to a spa.

The Fate of Cleopatra—The Duck Reveal

The ending of Freaks is one of the most jarring images in cinema history. We jump forward in time. Cleopatra is no longer the beautiful trapeze artist. She is now a performer herself—a squawking, feathered, legless duck-woman in a pit.

The freaks didn’t just kill her; they transformed her. The film implies she has been mutilated and exhibited as a sideshow attraction, though the exact details are left deliberately ambiguous, turning her into one of them—but without the soul or the community. It’s a poetic, gruesome irony that leaves the audience gasping. It’s the ultimate be careful what you wish for ending, delivered with a cynical smirk by Browning.

The Fallout—When Hollywood Panicked

When Freaks was first screened, the reaction wasn’t “Bravo!” It was “Call an ambulance!”Studio-era legend claims that a woman left an early screening in distress and later blamed the film for a miscarriage, though this story has never been verified. Whether that’s true or just classic carny hype, the result was the same: MGM went into a full-scale retreat. They took the film, which originally ran about 90 minutes, and hacked it down to 64.

They cut out:

The Full Attack on Hercules: Some accounts suggest Hercules originally suffered a far more brutal fate, possibly mutilation, though no surviving footage confirms exactly what was depicted. In the final version, he just kind of disappears, though a later scene implies he’s singing soprano in the background.

More of the Duck-Woman: The transformation of Cleopatra was originally much more detailed and lingering.

The Extended Chants: Some of the longer sequences of the performers interacting were trimmed because the studio feared the audience couldn’t handle too much of them.

Despite the edits, the movie was a disaster at the box office. It remained effectively unavailable in the UK for decades. It was pulled from theaters. Tod Browning, the man who made Dracula, became persona non grata in Hollywood. He made a few more films, but the stink of Freaks never left him. The industry couldn’t forgive him for showing them something so raw, so real, and so unapologetically weird.

Why It’s the Ultimate Cult Classic

So, why are we still talking about a 90-year-old movie in a world of high-def gore and CGI dragons? Because Freaks has something most modern horror movies lack: authenticity.

1. The Subversion of the Monster

In the 1930s, monsters were things from outer space or ancient tombs. Browning flipped the script. He showed that the person who looks monstrous is often the most human, while the person who fits the standard of beauty can be a literal demon. It’s a theme that would later define the works of David Lynch, Guillermo del Toro, and even the Evil Dead series. It’s about the “Other” fighting back.

2. The Found Family Dynamic

Long before Vin Diesel was mumbling about family in a fast car, the cast of Freaks was living it. The bond between the performers is the emotional anchor of the film. They have their own laws, their own language, and an unbreakable code of loyalty.

3. The Visual Mastery

Even in its butchered 64-minute form, Freaks is gorgeous. The use of shadow, the dynamic low-angle and tracking shots during the rainstorm, and the sheer physicality of the performers create an atmosphere that is impossible to replicate. You can feel the dampness of the mud and the chill of the night air. It’s visceral filmmaking at its best.

Final Thoughts—The Living Legacy

Tod Browning’s Freaks is more than just a movie; it’s a testament to the power of the fringe. It survived being banned, heavily cut, and effectively buried by the very studio that commissioned it.

It tells us that being one of us isn’t about how you look or how many limbs you have. It’s about who you stand with when the storm hits and the knives come out. It’s about the community of the weird, the fellowship of the forgotten, and the glorious, messy reality of being human.

So, the next time you’re watching a horror flick and you see a character who doesn’t fit the mold, or a transformation that makes you lose your lunch, tip your hat to Tod Browning. He did it first, he did it with real people, and he did it so well that Hollywood is still scared of him.

“Gooble-gobble, one of us!”

Now and forever.

Leave a Reply