Tag: Hammer Horror

-

By 1968, Hammer Films was standing on unstable ground. The Gothic cathedral they had spent a decade building—brick by blood-soaked brick—was beginning to crack. The world was changing faster than the studio could repaint its castle walls. Youth culture had turned feral. Authority was suspect. Faith was eroding. Horror itself was mutating into something colder,…

-

By late 1967, the Gothic castle was starting to feel a bit too safe. The shadows of Transylvania were familiar, almost comforting; they belonged to the world of velvet, candlelight, and ancient, predictable curses. To truly terrify an audience staring down the barrel of the Space Age, Hammer had to dig deeper—literally. They had to…

-

By 1967, Hammer’s Gothic cathedral was no longer echoing with hymns. The incense had burned low. The blood on the altar had dried into habit. What once felt transgressive, lush, and sacramental was now being gnawed away by a harsher, less forgiving reality. The world had changed, and Hammer—slowly, reluctantly—was beginning to understand that it…

-

By 1967, the Hammer Frankenstein cycle stood at its most philosophical precipice. Following the commercial necessities of The Evil of Frankenstein (1964), the studio and, crucially, Terence Fisher and Peter Cushing, needed to return the series to its roots: not in the spectacle of electricity and muscle, but in the harrowing inquiry into the nature…

-

By 1966, the Gothic heart of Hammer Films was due for a massive, necessary shock. Following the commercial necessity of the psychological thrillers (The Nanny, Hysteria) and the (unfairly called) misstep of a sequel like The Brides of Dracula (1960)—which dared to feature a world without the Count—the studio was compelled to confront the simple,…

-

By 1965, the Gothic machinery of Hammer Films, which had once felt like a bold revolutionary engine, now risked becoming a repetitive ritual. Audiences, glutted on blood and capes, were demanding a different kind of terror—one closer to home, stripped of historical distance and supernatural alibis. The genre had been redefined by Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho…

-

By 1964, Hammer’s Gothic machinery was running on instinct, guided less by inspired vision and more by the relentless momentum of commercial demand. The studio had resurrected monsters, seduced the dead, and given Technicolor blood a moral weight it hadn’t known before. Yet as The Curse of the Mummy’s Tomb emerged from the venerable, dust-shrouded…

-

By 1964, Hammer Films stood at a crossroads. The great Gothic cathedral they had built—of blood, faith, and moral dread—was showing its cracks. Dracula and Frankenstein had already carved their myths deep into British cinematic history, terrifying and scandalizing audiences across the globe. Yet the hunger for more persisted. The world demanded another resurrection, another…

-

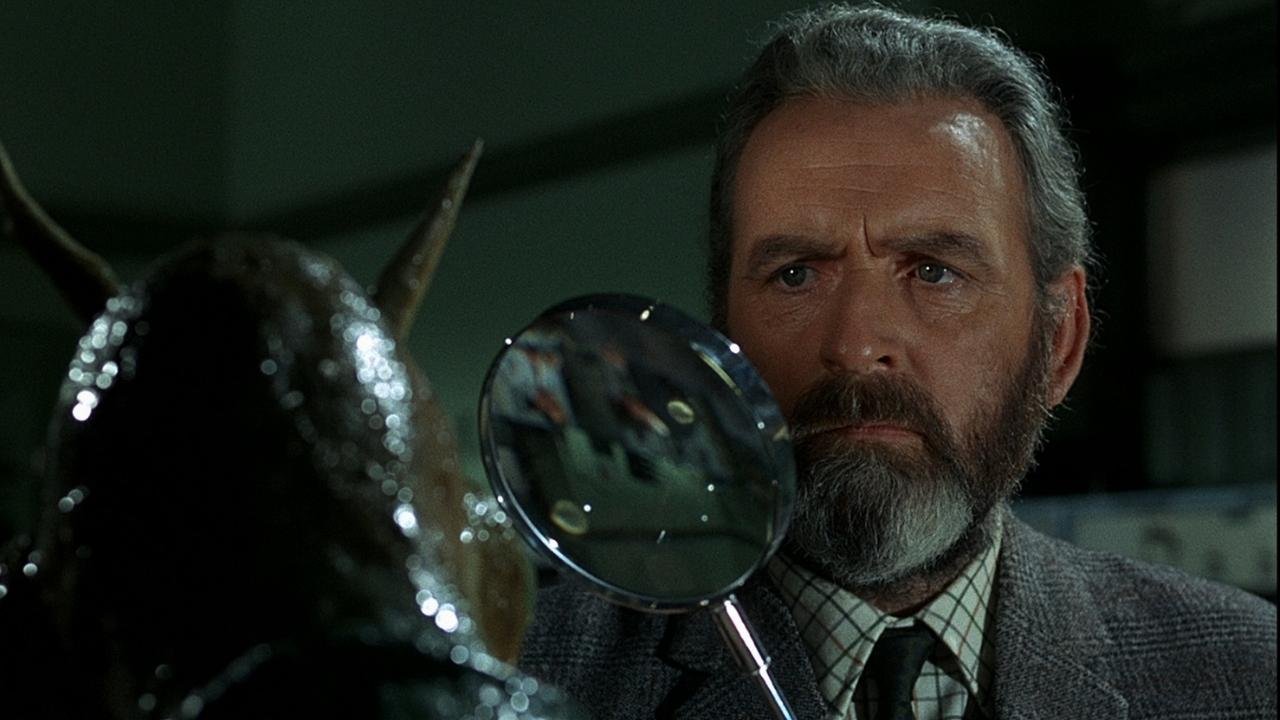

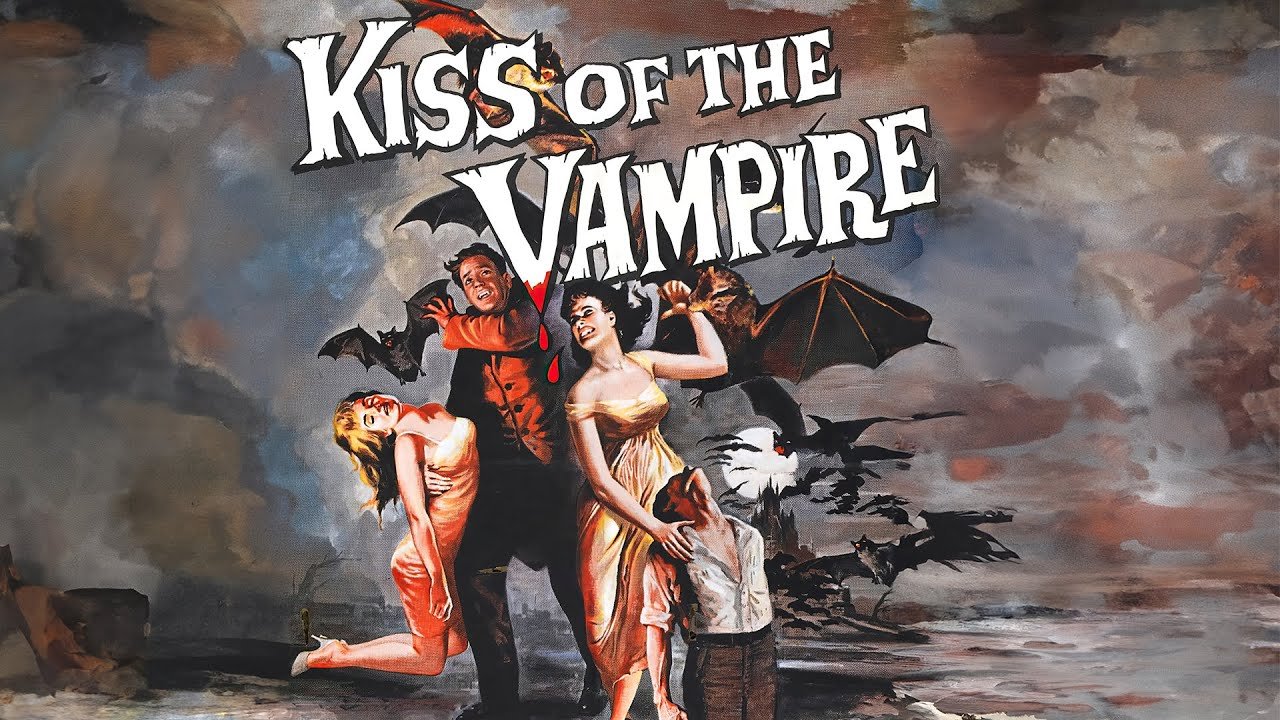

By 1963, Hammer’s cathedral of Gothic horror stood tall. Dracula had already bared its fangs to the world; Frankenstein had resurrected the flesh of gods; The Phantom of the Opera had mourned beauty’s decay beneath the stage. But now, with The Kiss of the Vampire, Hammer stepped into a new chamber — one where the…

-

By 1962, Hammer’s Gothic world had already been soaked in blood and revelation. Dracula and Frankenstein had rewritten the language of British horror; The Curse of the Werewolf had turned that language into lamentation. And then came The Phantom of the Opera — not a storm of violence, but a sigh. Terence Fisher’s Phantom is the…